Text

There is nothing more practical than a good theory, and the one I encountered in 1976 was no different. Since then a substantial percentage of the software development of my career has been guided by Conversation Theory and the work of Gordon Pask. In this paper I revisit my excitement in learning a theory that gave immediate prescriptions for the construction of training systems and adaptive, personalized information browsers. It was Pask who inspired the construction of an information management system that had all the components of modern Web browsers, but with the added good sense to provide an organising principle for the hyperlinks—something the World Wide Web still needs. Named after Pask’s first implementation, this THOUGHTSTICKER system was built in 1985, some 10 years before the Web’s acceptance. At the same time, techniques for modelling the user’s unique experiences and conceptual learning style gave embodiment to the concept of “personal computer.” THOUGHTSTICKER’s rich and humanistic interpretation of that common term is still unattained in commercial software products.

Over a 15-year period, many software prototypes were constructed and gave proof to the applicability of Pask’s theory. It remains to be seen if these and other aspects of his theory will rise to the consciousness of researchers and, ultimately, the marketplace—where his innovations would inevitably become popular and, afterwards, irremovable and “obvious.” This paper explains how, already, they are practical.

I entered the field of cybernetics as no doubt everyone does,as an observer of my own thinking. I was a few years old, I suppose.Later I spent time in the library, studying diagrams of “rat-in-a-maze” hardware artifacts. The logic of a system that made fewer mistakes over time, finding the shortest path to the goal, was fascinating to me. A goal-directed system, and one which learned, and which could be constructed as an artifact, seemed somehow sublime.

I entered the field of cybernetics as everyone does, as an observer of my own thinking. When I entered college, MIT was a swirling place, swirling with ideas on everyone’s mind, technology in every corner.

Certain classes were de rigueur no matter what your primary discipline or interest. Hans Lukas Teuber, talking psychology with stories of Conrad Lorenz and the goslings, was most entertaining. Psychology was concerned with my concerns, how we learn things and all; how we manage to talk to each other and ourselves. But “psych” never captured the feeling of my knowing, and never seemed to prescribe how to reproduce it in an artifact. Its notion of “staying objective” seemed unrealistic to me, a construction based on desire (ironically enough), and not on the achievable.

Computers seemed a more likely substrate for thinking about thinking, and in this domain Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, talking symbolic programming and artificial intelligence, were kings. They lectured in tag-team format, one of them punching out an idea until it was on the ropes, then the other guy stepping in to take care of the next one. I don’t remember very much of the detail of what they said; but clearly they were very smart, and had thought a great deal about problems of machine learning.

Wanting to design my own software rat-in-a-maze, I jumped into computer science coursework in earnest. But it was sitting directly at the machines, with that noisy typewriter in front of huge racks with blinking lights, that gave me the greatest pleasure.

Then I heard about Jerry Lettvin, an M.D. without PhD (said to be the only MIT professor without one) who taught in the Biology Department, and Humanities Department, and Electrical Engineering. My formal education in cybernetics began. It was Jerry who introduced me to concepts of the field, though to my memory he never emphasized, or maybe never even used the term “cybernetics.” But here, in the spell of his weekly classes, the organism was no longer an input/output machine; rather it was part of a loop from perception to action and back again to perception. Jerry’s method of “teaching ” appeared to be one of building arguments; but it was really a seduction. You could only love the ideas that came from him, because they caressed your thinking. He spoke of looking at one’s thumb as a closing of the nervous system through the environment—it was decades before I appreciated what that meant, but it stuck with me. 1

When I met Gordon Pask and then dived into his work, I realized that I had been well prepared by Lettvin’s seductions on perception and epistemology. I had heard well ahead that Pask was coming to consult with the MIT lab that I had joined after completing an undergraduate degree. Many stories were prologue to his appearance. He was difficult to understand but obviously brilliant, they said; he worked nights, slept days, they said; he lived pharmaceutically. He was coming to consult with us about the lab’s directions at the behest of Nicholas Negroponte, director of this lab called the Architecture Machine Group (a predecessor to Negroponte’s MIT Media Lab). I walked into Nicholas’s office one day to find Pask standing at a desk, looking down at papers with his head tilted while he ignited and drew deeply from his peculiar metal pipe. Nicholas introduced me to Pask as an actor, and introduced Pask as a producer and writer for the stage. “Hello, how do?”, Gordon Pask said to me, his gaze reaching toward me. His aura was both friendly sprite and probing sorcerer. Gordon Pask was to be my guide into the depths of cybernetics.

I became a student of Pask as no doubt countless others had begun: listening to his fascinating monologues, beguiling as much for what was not understood as for what was. Conversations held in noisy bars, straining to hear. Papers offered in the middle of the night from suitcases full of tobacco tins, clothing jumbles and electrical supplies. I began to read the papers, put them down, pick them up again weeks later. My interest was raised with each encounter. I had previously been steeped in all the hardware and software and concepts that MIT could offer; and in a matter of months, nothing was more interesting than what Gordon had. And that was so much: a theatrical existence, an audacious theory, an artistic sensibility. And most useful of all, given where I was at that moment, I could read his papers and write code. That is the central story of this paper.

When I met Pask I was working on problems of software user interface design. How does the user tell the software what to do? How does the software tell the user what it can do? The metaphor of “conversation” is of course immediately useful, and I got that from Pask and his papers on Conversation Theory. I was in the midst of designing an animation system and immediately adopted the form (if not the formalism) of his “entailment meshes” as a useful representation for animation scripts. 2

Entailment meshes, at least in their broad basics, are well documented in published accounts. 3 4 5 6 7

Entailment meshes were a revelation to me. They consist of abstractions and distillations of thought processes, which Pask quite intentionally named ‘concepts’, ‘topics’, ‘analogies’ and the like. Topics are grouped into relations, such as ‘analogies’ and ‘coherences’, that comprise concepts (‘concepts’) in a mental repertoire. His intention was to conjure common-sense meanings of these words, and also to provide details of how these usually ineffable notions could be made concrete and measurable. 8 Of course the details are far more subtle than that, and Pask provides great specificity to the whole nature and evolution of entailment meshes. 9

Entailment meshes gave me a way to focus on my thinking, and to represent it specifically, tangibly. Because meshes are derived from an elicitation process, they invest in the evolutionary and subjective nature of individual knowledge, not an absolute or external “truth” as in the “realist” perspectives of philosophy. 10 Here was an abstraction that felt right, whose subjective nature fit with my experience and sensibility. Because they were about the production and reproduction of concepts, entailment meshes could provide a dynamic model of what it means to know something: not merely the retrieval of structure or content out of a database (the “artificial intelligence” model, one might say) but rather the kinetic recomputation of individualized knowing. Later I learned that Heinz von Foerster had laid the groundwork for this, with the application of Eigen functions to model the stable processes of the nervous system. 11 The relationship of Pask’s work to von Foerster’s (and Humberto Maturana’s for that matter) is a fertile yet largely unexplored subject. 12 But Pask developed this notion in great detail, to the point of decomposing “knowledge acquisition” into operations of distinction-making, procedure building and the like. His diagrams for the sharing of simple concepts are remarkable, breathtaking in their specificity. 13

Once you go to the trouble of having a representation of a domain, you might do lots of useful things with it. Pask used it in studies of educational processes to offer experimental subjects a variety of ways of moving through a subject matter that they were trying to learn. 14 The ways of navigating the subject matter were as varied as the individual cognitive styles of the learners, and that was the point: to provide a means for students to learn in their own style, a capability not achieved in commercial training software to this day.

Another useful thing about domain models represented in an entailment or knowledge structure is that you can record the excursions that an individual makes by marking the nodes of the representation—a personal history of navigating through a domain. Then, when the individual student performs a further navigating action, the software can respond to that individual based on that history. This I claim achieves a genuine kind of personalization that commercial software tends not to achieve (even in today’s so-called “push technology”, for which “personalization” is erroneously claimed). If I were sitting in front of you now in a human-to-human conversation and responding to your question, should I give you the same answer I would give anyone else? Should I give you the same answer no matter what the previous question was? Shall I just ignore what I have observed in our previous conversations about what is an effective conversation with you? Behaving as poorly as this, these machines are what we call “personal computers.” That is of course a deception; computers of standard commercial fare are merely impersonal ones.

Negroponte adopted Pask’s notion of personalization by means of his own phrase, “idiosyncratic computers”, a perfectly apt term. On this and other occasions, he tried to incorporate Pask’s ideas into the lab’s ideas. The lab worked with Pask to construct a research proposal submitted to the US National Science Foundation. Merging the research lab’s interest in computer graphics with the Paskian framework, the proposal was called Graphical Conversation Theory. We submitted perhaps the best graphically-designed proposal ever (and were criticized for it). The reviewers were split, one calling it brilliant and important to the future of user interface design; another calling it disorganized and uncertain as to its potential outcome. Both were right, but the Foundation chose against taking any risk, and declined funding.

Feeling that I had exhausted the intellectual possibilities at MIT, I moved to New York City and began frequent trips to Pask’s research organization, System Research Ltd, UK. I was wide-eyed, I am sure. I correctly guessed that I would not be the first to arrive so, a neophyte wishing to become involved with The Maestro in some capacity or other. The lab in his home’s basement in Richmond-upon-Thames was unique among research labs for its innovative and compelling use of relatively simple technology, as well as its ambiance: the old machines lying about, semi-cannibalized for newer incarnations; the lack of any housekeeping; the creeping damp.

Some of those crusty machines were revelations. The Steam Engine was an electro-mechanical simulation, with lights and moving parts and user-controlled parameters, which were the basis for understanding the workings of a real steam engine. Long before simulation was practical in common computers, or pounced upon as a sensible means for using software and computer graphics to teach how systems work, here was Pask forging ahead with wires and motors and lights.

Here too was the first incarnation of THOUGHTSTICKER, a software environment based on entailment meshes. This version was a conceptual innovation, perhaps, but surely not a technical one. There was insufficient storage (flexible, not hard disk in those days, or RAM) in the mini-computer to allow for electronic display of a subject matter, but this was no discouragement to the implementors. The processor simply controlled a row of lights above a row of cubbyholes, each one containing a clipboard with a piece of paper on which the content was printed. The user responded to a lighted cubbyhole by extracting the clipboard and reading the material.

This THOUGHTSTICKER possessed display hardware that was obsolete at Negroponte’s lab and shipped to System Research for dynamic displays of Paskian nature. An incessant software bug, which Pask contended was a “feature” and led to extraneous lines in these displays, did little to discourage the imagination to think that, with decent funding, something really amazing could be done here.

So System Research was given a contract by a group of psychologists in the UK Admiralty. They saw that existing approaches to their problems were too limiting, and were intrigued by what Pask might offer. And that is where I found my place: representative of America’s technological prowess, and erstwhile interlocutor between The Maestro and those interested in applying his ideas. Could domain representations be a practical way to improve strategic training systems? Could a re-implementation of THOUGHTSTICKER in a sensible (and reproducible, and reliable, and documented) environment provide an advance in capability? Could Pask stay with a client’s problem long enough to complete a useful prototype?

Typically for any Paskian adventure, the answer was yes and no. Later, within the context of a consultancy that I established to continue the work, we did manage to build a sophisticated version of THOUGHTSTICKER in LISP, in the programming development environment sold by Symbolics, Inc. 15 Pask continued as consultant and advisor, keeping us on track within our limits and those of any single-processor implementation of concepts that really required wholly new hardware architectures. 16

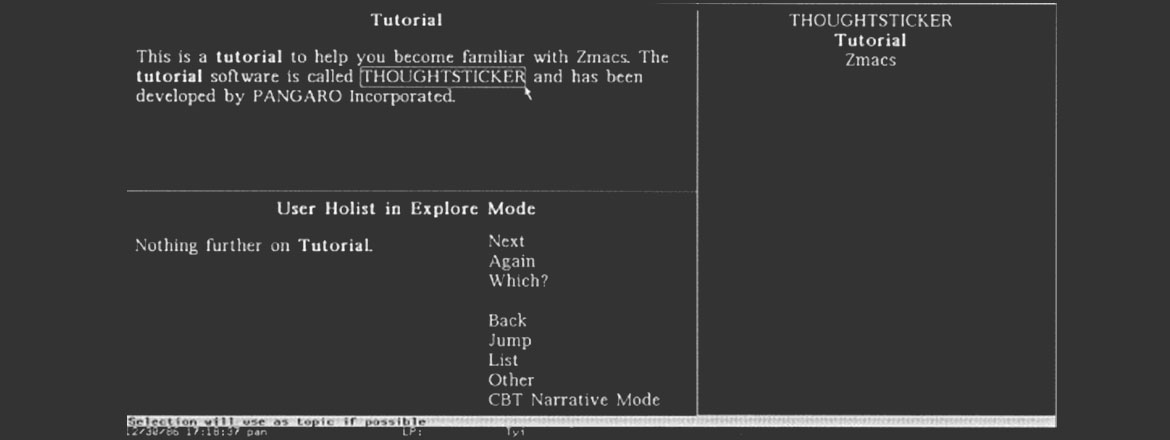

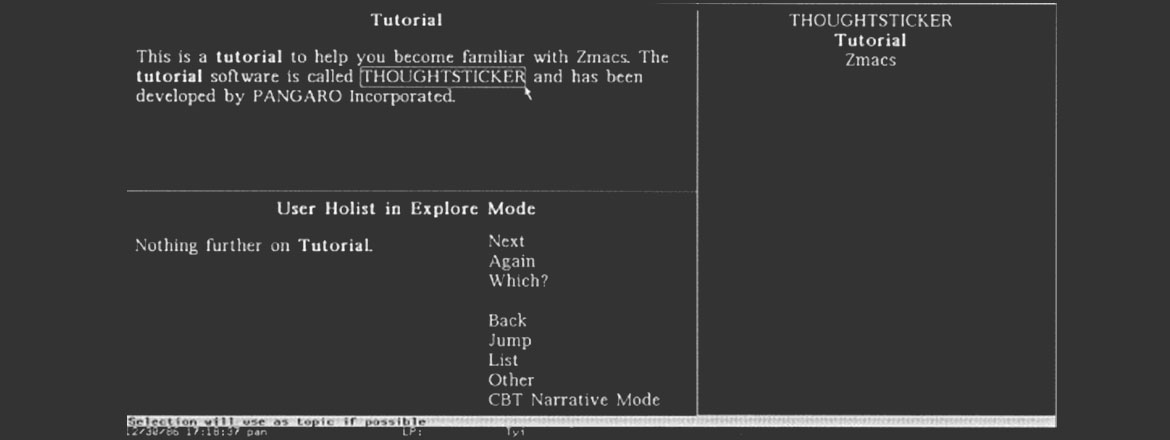

Here is a screen shot from our THOUGHTSTICKER circa 1986. We called this “Naive THOUGHTSTICKER” because our sponsors considered that what we had built before required too much knowledge of the underlying scheme. They were right, of course, and while extracting the essence of the Paskian ideas, the user interface design that we “uncovered” (rather than “created”) became an early information browser with the look-and-feel of modern Web browsers. 17

It is not possible to give the software full justice in print; other explanations available elsewhere partially remedy this fault.

In addition to features that are now commonly, nay, universally found in Web browsers, there are some that have yet to be considered for commercial markets. Here is a brief review of the THOUGHTSTICKER functions available from its main user interface in 1986:

There are two significant differences between today’s Web browsers and THOUGHTSTICKER circa 1986. First, entailment meshes represent an organising principle for the structure of content in information design. Instead of the pure anarchy of arbitrary hyperlinks across Web pages, THOUGHTSTICKER provides a reason for composing specific content in a single page-view (namely, the structuring provided by topics, concepts, and all the other rules of coherence and distinction in entailment meshes, as noted above).

An important consequence of having this structure is the ability to track an individual user’s navigation through a subject matter domain, and to build a model of that user on which subsequent actions of THOUGHTSTICKER can be based. This is the basis for making hyperlinks that are not static connections as pre-determined by the content designer for all users to be the same. Instead, and as noted above, clicking on a THOUGHTSTICKER link would produce one result for one user, and very likely 18 a different result for another user. This would depend on 3 mechanisms, here described in the original words of the materials 19 prepared for dissemination in 1987:

If Web browsers had these THOUGHTSTICKER functions, the experience of information browsing would be wholly different.

One summary description of THOUGHTSTICKER as a personalized browser could be given in terms of the regulation of the degree of measurable uncertainty presented to the user at any given moment. THOUGHTSTICKER can be described as an adaptive teaching machine capable of maximizing the likelihood of learning at each presentation by minimizing the user’s uncertainty.

‘Uncertainty’ is a multi-dimensional measure, and may involve:

All together THOUGHTSTICKER had around twenty such uncertainty measures, some of which were overlapping. The basis of all THOUGHTSTICKER’s adaptive qualities, and hence the personalization, sensitivity to individual cognitive style, and “conversational sensibility”, can be viewed as aspects of regulating uncertainty on behalf of the user.

It should be remembered that there are limits to what can be measured or inferred about an individual’s current cognitive situation, and hence where that individual’s uncertainty lies. Furthermore, “learning to learn” functions (where the student is encouraged to move beyond existing limitations of learning style) would require that some choices by the system would be made not to minimize uncertainty, but rather to “stretch” the user’s experience with content that challenges the user’s predominant learning style. We did not get around to adding this “meta-adaptation” to THOUGHTSTICKER functions.

Taking advantage of entailment meshes to produce the above features of adaptive, personalized training is not surprising, given their heritage in cognitive modelling and learning style research. What is not apparent in those features, however, is the set of content-creation aids that THOUGHTSTICKER provides as a consequence of entailment meshes being a dynamic modeling tool for the evolution of knowledge structures. THOUGHTSTICKER can provide highly sophisticated aids to the process of creating the subject matter domain model itself.

My colleagues and I have argued that conventional computer-based training (CBT) provides nothing by way of stimulation for the author; it is merely content repository consisting of whatever the subject matter expert might wish to say about a domain. In contrast, THOUGHTSTICKER actually stimulates the author to be consistent and complete. One consequence is that THOUGHTSTICKER is by far the most efficient environment for authoring, compared to AI-based training (“Intelligent Tutoring Systems” or ITS) as well as CBT. 21

To understand how these active catalysts to authoring work, imagine the basic content-creation process for a subject matter expert. A primary authoring activity is that of composing prose explanations. (This is not necessarily the first authoring step; the author may prefer to create distinctions and structures first, and user-viewed content later. The advantages claimed still apply no matter the preferred method, including a mix of methods over time.) Imagine then a word-processing window that has all the smarts of entailment mesh logic behind it, as the author is typing.

Here then is the sequence of active processing that THOUGHTSTICKER undertakes by way of stimulating the author in the domain- modelling process:

Unique to THOUGHTSTICKER, the combination of these features make the process of creating the subject matter much more efficient, as well as more effective, than passive authoring environments. The result is nearly a “conversational protagonist.” In addition, multiple authors, possibly at different sites, can contribute to the same knowledgebase without interfering with each other. Plus the original knowledgebase can be augmented and tailored to differing needs at different locations.

Note the emphasis on, and distinctions around, the identity of the individual author. THOUGHTSTICKER keeps individual author’s identities distinct, and so can produce responses of the form, “A similar statement was made by so-and-so author on such-and-such a date; would you like to see that statement?” (further described below). And this leads into perhaps the most profound contribution of entailment meshes to mental modelling and knowledge acquisition, that of contradiction detection and resolution.

In certain cases THOUGHTSTICKER can detect a possible conflict between statements. Technically speaking, it does this not by the semantics of the text but the structures of the knowledgebase that the text expresses (as noted above, THOUGHTSTICKER does not contain natural language processing). The system offers a series of methods to resolve the conflict depending on the structures: statements may be declared “not accepted”, they may be merged with others, distinctions may be added, etc.

Here follows a dialog taken directly from the action of the THOUGHTSTICKER software. This is a simplification of the actual working of THOUGHTSTICKER, because it is inconvenient to represent all the display panes and movements of data through those panes in anything less than a video. The simplification has a number of aspects. For example, the implication below is that all responses had to be typed; however, the user could click on the text to answer a question posed by the software. Also, different options taken in a branching tree of responses cannot all be explicated, though the direction that the software would take is noted for significant cases. The exchange given below does however accurately express the workings of THOUGHTSTICKER as an elicitation partner, based on the distinction logic and contradiction detection of Pask’s underlying knowledge representation scheme.

The two left columns replay what THOUGHTSTICKER types and what the user types, respectively; the right-most column describes the action taken by the software. This scenario is taken directly from a real demonstration of the software with a user called ‘GP’, and THOUGHTSTICKER’s responses are based solely on the user’s typing and its internal procedures.

| THOUGHTSTICKER | User called ‘GP’ | THOUGHTSTICKER Action |

|---|---|---|

| Describe a topic | sky | Instantiates ‘sky’ as a topic |

| What is significant about ‘sky’? | The color of the sky is blue. | Records the statement |

| What topics do you wish to distinguish in this explanation? | color | Does not find ‘color’ as a pre-existing topic; instantiates it as a topic |

| The topic ‘color’ is unknown; do you wish to give an explanation for it? | Yes | Displays a fresh pane in which to accept a new explanation |

| Type your explanation of ‘color.’ | Reflected light of a particular wavelength. The color of something may be red, blue, green, yellow or any other word that expresses the experience of eye. | Records the text |

| Returning to your previous statement, about ‘sky.’ | Displays the original sentence, ‘The color of the sky is blue.’ | |

| What further topics do you wish to distinguish in this explanation? | blue | Does not find ‘blue’ as a pre-existing topic; instantiates it |

| The topic ‘blue’ is unknown; do you wish to give an explanation for it? | No | |

| What further topics do you wish to distinguish in this explanation? | None | Instantiates a concept that consists of ‘color’, ‘sky’ and ‘blue’; attaches the statement to the concept |

| Your statement about ‘sky’ is accepted. |

Nothing remarkable so far. Upon browsing this domain, any user would find the above concept (the relation of ‘color’, ‘sky’ and ‘blue’) as expressed in the statement ‘The color of the sky is blue.’

Now imagine that a different user called ‘RG’ has logged into THOUGHTSTICKER and also wishes to author some material.

| THOUGHTSTICKER | User called ‘RG’ | THOUGHTSTICKER Action |

|---|---|---|

| Describe a topic | sky | Finds ‘sky’ in its existing entailment mesh; tallies it in new list of topics |

| The topic ‘sky’ has been described by user ‘GP.’ Do you wish to explore that description? | No | |

| What is significant about ’sky;? | The color of the sky is red. | Records the text statement |

| The topic ‘color’ is detected; is it significant to your explanation? | Yes | Tallies ‘color’ |

| What further topics do you wish to distinguish in this explanation? | red | Does not find ‘red’ as a pre-existing topic; instantiates it |

| The topic ‘red’ is unknown; do you wish to give an explanation for it? | No | |

| What further topics do you wish to distinguish in this explanation? | None | Compares the concept ‘color’, ‘sky’ and ‘red’ to the pre-existing entailments; finds a potential contradiction with ‘color’, ‘sky’ and ‘blue’ |

| Your statement may conflict with another statement, made by user ‘GP.’ That statement is ‘The color of the sky is blue.” Do you wish to keep that statement | Yes | |

| Are ‘blue’ and ‘red’ synonyms? | No | [If the user had replied ‘Yes’, the system would instantiate a synonym between the topics and elicit further details for the analogy] |

| Is ‘color’ different in each statement? | No | [If the user had replied ‘Yes’, the system would instantiate an analogy between the two instances of ‘color’, elicit further details for the analogy including a statement to present it in future, and allow the statements to be modified - in the current user’s context only] |

| Is ‘sky’ different in each statement? | No | [Ditto to the above] |

| Are there any topics you wish to add to your statement? | Yes | |

| What topics do you wish to add? | Mars | Does not find Mars as a pre-existing topic; instantiates it |

| The topic ‘Mars’ is unknown; do you wish to give an explanation for it? | No | |

| Do you wish to modify your statement? | Yes | Displays text buffer for modification of statement |

| What is your new statement? | The color of the sky is red on Mars. | Instantiates a concept that consists of ‘color’, ‘sky’, ‘red’ and ‘Mars’ and attaches the statement to it. |

| Statement accepted. |

THOUGHTSTICKER contained a large logic tree of how to handle the various possible responses (both those indicated and others), in order to construct an entailment mesh consistent with Pask’s notions.

They may be ubiquitous, multi-media rich and standardized everywhere, but (I repeat) today’s browsers do not have what Pask’s entailments can bring to them: an organizing principle and the fine-grained, adaptive nature of a conversation. Browsers will continue to move to a meaning of “personalization” far closer to what Pask presaged and designed a substrate for, long before we knew we needed it. Commercial technology for authoring and annotation, now the focus of an emerging Web standard called WEBDav, similarly lacks the catalytic functions of THOUGHTSTICKER. Commercial technologies will continue to evolve and will move, I feel certain, toward what Conversation Theory could give them now.

This is an issue for cybernetics, it seems, era after era: new ideas, too amazing to be absorbed at the time of their initial form, later emerge but in different terms and different disciplines, and usually without attribution.

Just as the stories above provide only a partial review of the systems described, mention of a further application for Conversation Theory can only sketch its value.

Consider that entailment meshes represent snapshots of a constantly evolving state of knowing. Conversation Theory, if it is to be complete, must provide models of mechanisms for transitions from one state of knowing to another, and the contradiction resolution dialog recounted above is one view.

Just as entailments model a state of knowing, the dual of entailments, called the architecture of conversations, captures the structure of the interactions across the perspectives that are necessary and inherent in the creation of these states of knowing. To evolve from one state to another (“to learn”) involves the exchange of information across perspectives represented in the conversation. To model any learning, from rat-in-a-maze path minimization to team problem solving, entailment meshes plus conversational interactions comprise a necessary and sufficient set of views of that learning.

Other published papers 23 have succeeded in clearly expressing this architecture. My point here is that, if taken seriously as a modeling tool for systems such as corporations and families and project teams, this architecture of conversations could become the basis of an innovation in software. Such as system would serve up the power of a cybernetic methodology, capable of encompassing both subjective and objective interactions among system elements of all kinds (teams, humans, machines, artifacts).

Is this wanted? Consider that once the basic problems of number crunching and word processing applications were solved, the software industry and its customers were ready to move toward networks, and then to collaboration software. The current buzz around “knowledge management” is occurring because lower levels of needs have been fulfilled, and further capabilities that require these substrates can be next. By extension, once process models such as workflow are easily made robust and available, corporations (at least) will be interested in software-based models of their goals as well as their processes.

Pask’s conversational architecture is the same type of detailed prescription for goal-directed organizational modelling that his entailment meshes were for adaptive, self-organized information browsing. Elsewhere 24 I have described an application of Conversation Theory to organizational modelling, and over the twenty years that I have pondered this notion and used it as the basis of mostly manual (that is, not a software-based) facilitation, I see the modern corporation and the software industry converging on it on their own. No one can predict whether the terms Paskian or Conversation Theory will be associated with it when it arrives, and I prefer to avoid any nostalgic regret should that not occur in my lifetime.

But if the world someday recognizes Pask, I don’t doubt that his model of consciousness will be found useful. 25